Pluto Data

- Average distance from the Sun: 39.5 x Earth distance

- Orbital period: 248 years

- Diameter: 0.19 x Earth diameter

- Mass: 0.0022 x Earth mass

- Rotation period: 6.4 hours

- Average density: 1.9 g/cm3

- Composition: ice-rich (about 70% rock, 30% ice)

- Cloud-top temperature: –230°C

- Moons: 5

Comet Data

- Location: Two major regions: (1) Kuiper belt beyond Neptune; (2) Oort cloud, much farther out.

- Sizes: Wide range, from boulders to dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris.

- Compositions: ice-rich (mixtures of ice and rock)

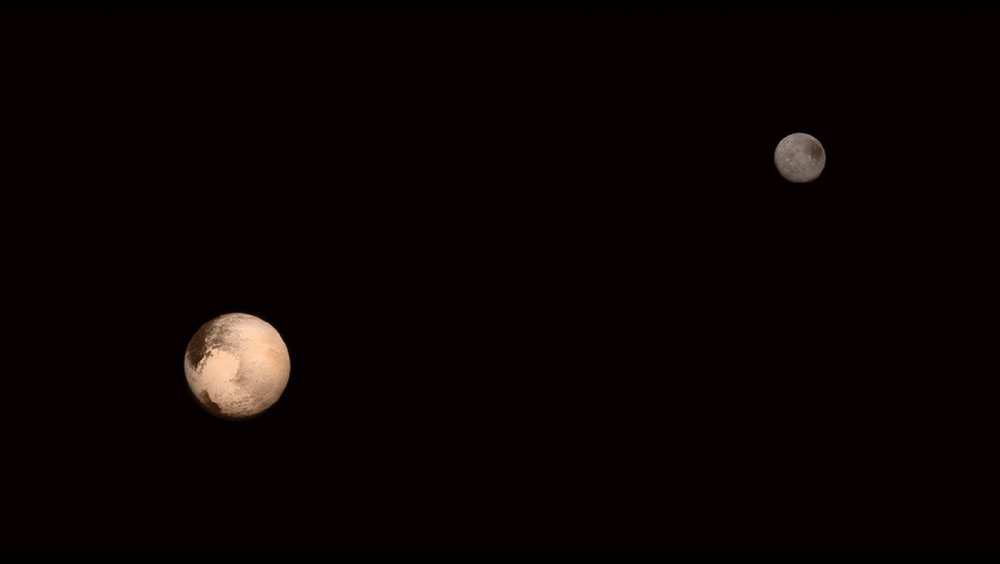

We conclude our tour at Pluto, which was discovered in 1930 and considered for some 75 years to be the “ninth planet” in our solar system. However, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union voted to demote Pluto to being a “dwarf planet.” To understand why, we need to talk a little bit about comets.

Although the comets we occasionally see in the night sky have come into the inner solar system, most comets remain forever far from the Sun. In fact, by studying the orbits of the rare comets that appear in our sky, scientists have learned that comets come from two major regions in our solar system: The Kuiper belt (“Kuiper” rhymes with “piper”), a donut shaped region containing hundreds of thousands of comets that lies just beyond Neptune, and the Oort cloud (“Oort” rhymes with “court”), a spherical region with billions of comets that lies much farther out.

Pluto lies within the Kuiper belt, and its composition is very similar to that of other comets. In other words, Pluto is essentially an unusually large comet. But it is not the largest; Eris, discovered in 2005, is slightly more massive than Pluto. Indeed, it was the discovery of Eris that led to Pluto’s demotion, because astronomers realized that if Pluto was a planet, then Eris had to be as well. They decided instead to call both objects dwarf planets. More specifically, they decided that any asteroid or comet that is large enough to be round would be called a dwarf planet. That is why the asteroid Ceres counts as a dwarf planet; at least two other Kuiper belt comets (Makemake and Haumea) also count as dwarf planets, and there may be dozens of others, but astronomers are not yet sure if these objects are round.

Keep in mind that the fact that Pluto is called a dwarf planet does not make it any less interesting or important. In fact, the New Horizons mission discovered that Pluto is an astonishing world with active geology, a thin atmosphere, and possibly even a subsurface ocean. It is likely that many other large comets of the Kuiper belt are similarly interesting, and it is possible that we’ll someday also find incredible objects among the many comets of the Oort cloud.

Where’s the next planet? If you’ve reached Pluto in the Voyage model, you’ve already passed all eight official planets, since Neptune is the last on the list (with Pluto considered a “dwarf planet”). It remains possible that we’ll discover a ninth planet beyond Pluto in our solar system, but aside from that, you’d have to go to the next star to find more planets. How far is that? On the Voyage scale, in which you’ve probably been able to walk from the Sun to Pluto in just a few minutes, you would need to walk more than 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) just to reach the nearest star besides the Sun. That’s a distance equivalent to walking across the United States!